Three years before 9/11, the Taliban diplomatic envoy is expelled from Saudi Arabia over the refusal of the government in Kandahar to hand over Osama Bin Laden.

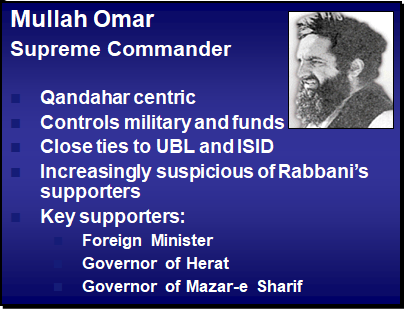

After the African embassy bombings in August 1998, Washington sought Saudi Arabia’s help in forging a break between the Taliban and bin Laden, specifically in getting Mullah Omar to eject bin Laden from the country.

Prince Turki bin Faisal (also known as Turki al-Faisal)—head of Saudi intelligence and bin Laden’s earlier sponsor during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan—went to Afghanistan to meet with Omar, head of the Taliban. The meeting is the stuff of legend, the powerful Saudi prince being not just rebuffed and insulted, but treated with less than princely dignity, and leaving in a swirl of robes.

When the Taliban ambassador was expelled from Riyadh, Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah happened to be in the United States on a visit and met at the White House with President Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. He reported on the earlier Turki visit to Afghanistan and expressed Saudi frustration with the unorthodox regime. Saudi Arabia wouldn’t formally break off diplomatic relations with the Taliban until September 25, 2001.