White House counterterrorism advisor Richard Clarke sends an urgent memo to Condoleezza Rice and deputy national security advisor Stephen Hadley warning that there are al Qaeda sleeper cells within the United States and of an impending terrorist attack on America soil.

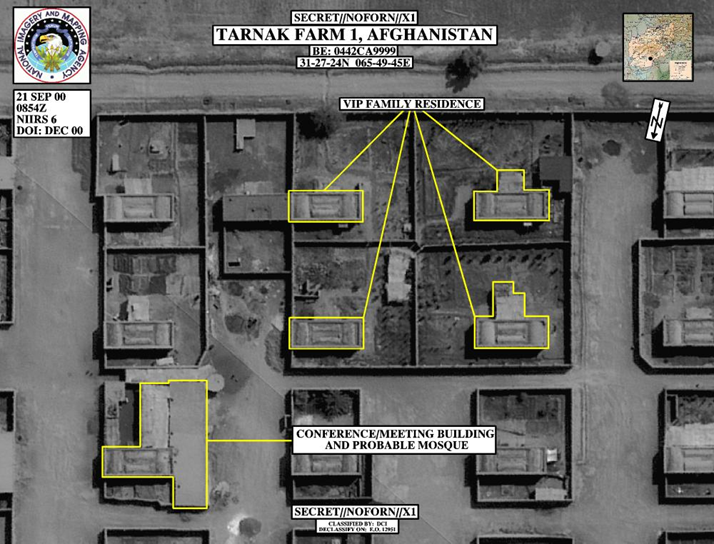

In a grand strategy paper on dealing with terrorism, Clarke advocates targeting al Qaeda training camps in response to the October attack on the USS Cole in Yemen. He proposes “rolling back” al Qaeda over a period of three to five years, proposes military action as well that would attack Taliban infrastructure. (At the Center of the Storm, p. 143)

Clarke writes that al Qaeda “is not some narrow, little terrorist issue that needs to be included in broader regional policy,” taking a jab at Rice’s concept of a “regional” solution to terrorism. He says that key decisions that had been deferred with the end of the Clinton administration dealing with covert aid to the Northern Alliance and the Uzbeks, to political messages to the Taliban and Pakistan, and new money for CIA operations need to be resolved regardless of larger policy.

Though the 9/11 Commission would say that Rice did not respond directly to Clarke’s memo and no principals committee meeting regarding al Qaeda took place until September 4 (911 Commission, p. 201), the truth was that Clarke’s memo presented nothing new and didn’t represent any new intelligence regarding the immediate threat. One can fail the Bush administration for not seriously engaging with the issue, but it is also the case that Clarke failed (as did CIA director George Tenet) to convince the new administration of the threat, later trumpeting so many warnings that they drowned the new administration. And in his January 25 memo, which the 9/11 Commission tartly labels “elaborate,” Clarke’s inclusion of his 2000 strategy and his 1998 plan annoyed Rice and Hadley, that it was both too stale and too narcissistic.