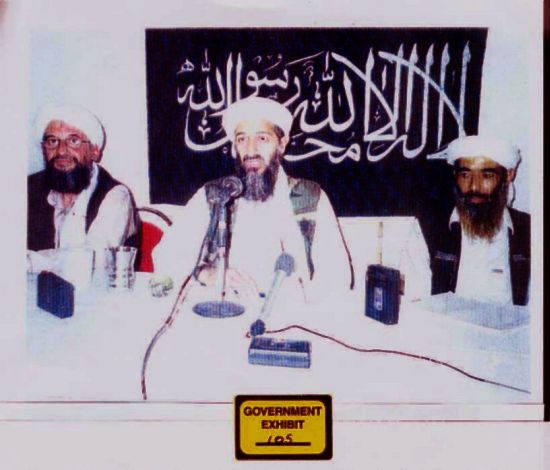

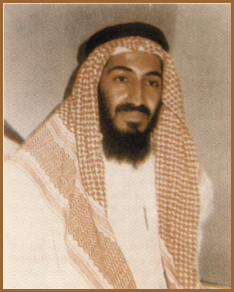

A year before 9/11, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) is appointed head of all media operations for al Qaeda. Between then and the attacks, he works with London and other Arab-based media in transmitting statements and distributing videos and cassettes.

The 34-year-old Pakistani national, who was raised in Kuwait and went to college in the United States, was by then an experienced operator for Osama bin Laden, having worked in Islamic aid organizations in Pakistan and Afghanistan during and after the Soviet occupation and then playing a hand in various plots, including the 1998 African embassy bombings.

Though indicted for terrorist conspiracy in 1996 by the Southern District of New York (for a plot to blow up American airliners over the Pacific), and even after a failed rendition attempt by the FBI, he is not a household-name terrorist, not even amongst CIA analysts, FBI investigators, or experts. And yet he is now universally accepted to have been the conceiver of the airline plot and the “teacher” of the Hamburg Three (Mohammed Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, and Ziad Jarrah) with regard to operational security and preparing their year-and-a-half long preparations in the United States.