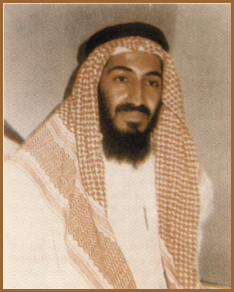

Osama bin Laden, an obscure 37-year-old ideologue from Saudi Arabia, began to write a series of open letters as “The Committee for Advice and Reform” to then-King Fahd, to prominent princes and religious figures in the country, and to “the people of the Saudi Arabian Peninsula.”

The publicly-shared letters, written between 1994 and 1998, begin to express bin Laden’s worldview and radicalism, first in publicly speaking out about the situation in Saudi Arabia, and second, in laying out a set of grievances that prevent Arab fighters in Afghanistan and Pakistan from returning to their home countries (with the end of the Soviet occupation).

Seven years before 9/11, bin Laden talks of the insults and “apostasy” of American military forces deployed to Saudi Arabia after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, and even accuses King Fahd of “wearing a cross.” He addresses corruption in the country, the uneven application of Shariah law, what he claims are overtures and accommodations with Israel, and even the poor state of the Saudi armed forces, given how much money Saudi Arabia has spent on arms.

“The gulf crisis [the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait] revealed the lack of preparedness, the need for [foreign] troops, and the ineptitude of its leadership. All of these shortcomings exist in spite of the astronomical amounts that have been spent on the military,” bin Laden wrote—all accurate portrayals and a reality that persists to this day as demonstrated in the disastrous Saudi-run war in Yemen.

“The regime also imported Christian women to defend it, thereby placing the army in the highest degree of shame, disgrace, and frustration,” bin Laden wrote, references to his own brand of fundamental Islam—what would become central to al Qaeda ideology.

The letters are rhetorical, inflammatory, and inaccurate to the Western reader but also a clear indictment of the family Saud and other Arab rulers. The letters in many ways are as erroneous as they are prescient in laying out bin Laden’s and al Qaeda’s grievances, but they are also so obscure in their focus and references that they were hardly noticed in the West. They form a rich source, and yet were little known, even after al Qaeda’s early attacks on America, certainly a missed opportunity to understand what drove so many to take up arms in this new brand of international and anti-American terrorism.