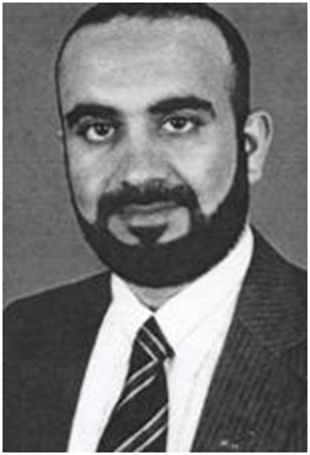

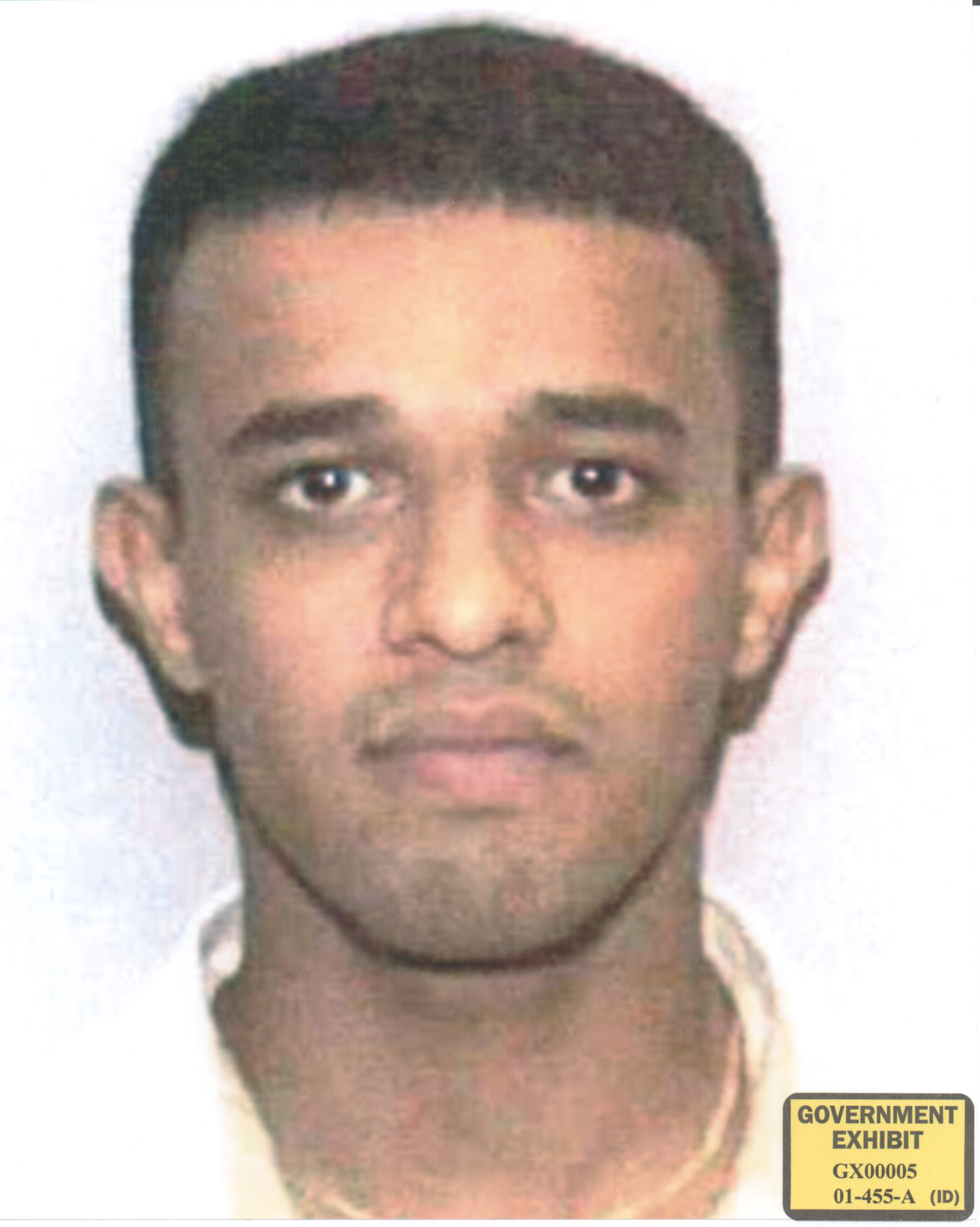

The first two hijackers associated with 9/11, Saudi nationals Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, arrive in the United States, 18 months before the attacks. The two arrive in Los Angeles on United Airline Flight 2 from Bangkok, Thailand.

Despite CIA admission (see January 13) that al-Mihdhar, a “known” al Qaeda operative, is on the loose, neither is ever put on any watchlist—that is, until days before the attacks in August 2001. But the real problem here is how the two could live in the United States for so long, even while the CIA and FBI exchange hundreds of emails and reports about them. (And then al-Mihdhar will actually leave the United States and return on another flight on July 4, 2001, a far more troublesome lapse for the counterterrorism watchers.

Al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar told immigration authorities at LAX that they would be staying at the Sheraton Hotel in Los Angeles. The FBI later found that their names never appeared in the hotel’s records. Then the FBI searched the records of other hotels near the airport, as well as smaller establishments in Culver City, failing to find any trail of the two as they reconstructed the road to 9/11.

They are, in fact, picked up by an intelligence officer of Saudi Arabia and taken to San Diego, residing in the officer’s apartment from January 15 to February 2, 2000. But then that’s another story.