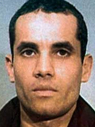

Ahmed Ressam, traveling on a Canadian passport under the name of Benni Antoine Noris, is arrested at Port Angeles, Washington at the U.S.-Canadian border. His car contains bomb-making chemicals and detonator components and he is entering the U.S. with the intention of blowing up a bomb at Los Angeles International Airport on New Year’s Eve.

Algerian native Ahmed Ressam is later found to have trained in Afghanistan al Qaeda camps in Khalden and Darunta, receiving instructions on bomb making and probably the Los Angeles assignment. His case involved terrible failures by French and Canadian authorities. Ressam managed to initially fly from France to Montreal using a photo-substituted French passport under another false name, that of Tahar Medijadi. Under questioning in Canada, he admitted that the passport was fraudulent and claimed political asylum. He was released pending a hearing, which he failed to attend. He was then arrested four times for pick-pocketing, usually from tourists, but was never jailed nor deported.

Ressam eventually obtained his genuine Canadian passport through a document vendor who stole a blank baptismal certificate from a Catholic church. He used the passport to travel to Pakistan, and from there to Afghanistan for his training, returning to Canada before attempting to enter the United States.

Though the CIA and others in the Clinton administration would later crow about the capture of Ressam, his arrest in Port Angeles was completely by chance, due to the work of an individual customs agent on the spot (who had never received any terrorist warnings from higher headquarters or Washington).

“In looking back,” George Tenet later wrote, “much more should have been made about the significance of this event. While Ressam’s plot was foiled, his arrest signaled that al Qaeda was coming here.” (At the Center of the Storm, p. 126)