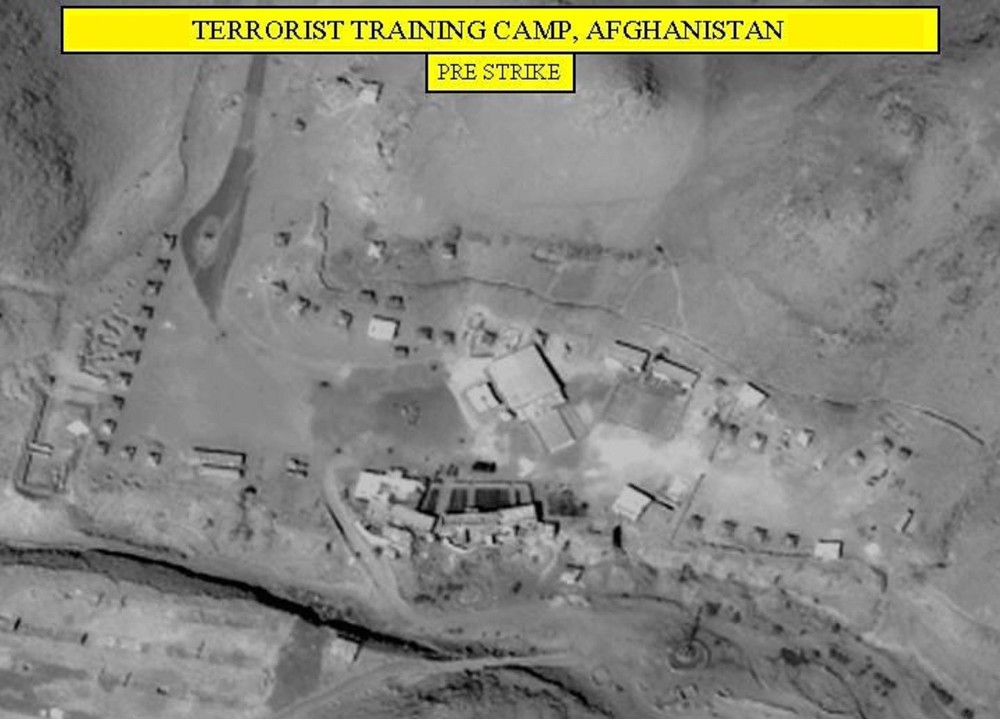

After the December 1998 decision was made not to use Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missiles in a strike in Afghanistan to target Osama bin Laden in Kandahar (fear of civilian collateral damage being the most important factor in rejecting the missiles), Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Henry (“Hugh”) Shelton directs the development of a new plan that would use an AC-130 gunship to assassinate bin Laden and be used in other retaliatory strikes. (911 Commission, p. 134)

The aircraft, operated by Air Force Special Operations Command, would in theory be able to use its cannons to inflict a more precise and intense attack. The precision of AC-130 gunships would later become a major factor in collateral-damage incidents during the Afghanistan war (and later in Iraq), as the aircraft proved not to be quite as precise as advertised. But more important, the special operations asset’s attacks and record get buried in official secrecy, the plane never being scrutinized alongside fighter aircraft and bombers.