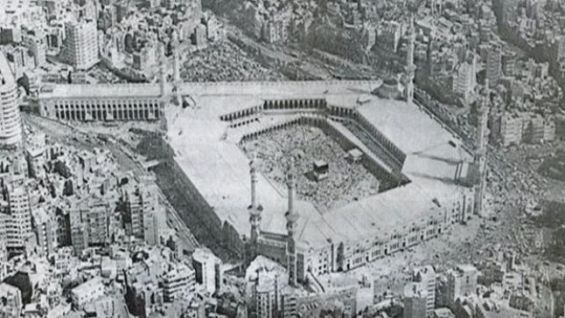

An obscure but seminal event occurs, when a group of Saudi dissidents—alternately called “Sunni Muslims,” “Muslim fundamentalists,” “Shi’a vermin from Hasa,” and even “foreign agents”—attack the Grand Mosque of Mecca, Islam’s holiest site.

Entering the walls of the mosque, some 200 rebels, mostly Saudis, but including Egyptians, Kuwaitis, Yemenis and Pakistanis take thousands hostage and barricade themselves inside. They call for the overthrow of the pro-Western Saudi government. It is an unprecedented event in Saudi history and the first mega-action by Islamic fundamentalists. And it is a seminal event for a young Osama bin Laden, who was reportedly shocked into a political awakening, one that became even more stark when a month later, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, while the standoff between Saudi forces and the hostage takers was still going on.

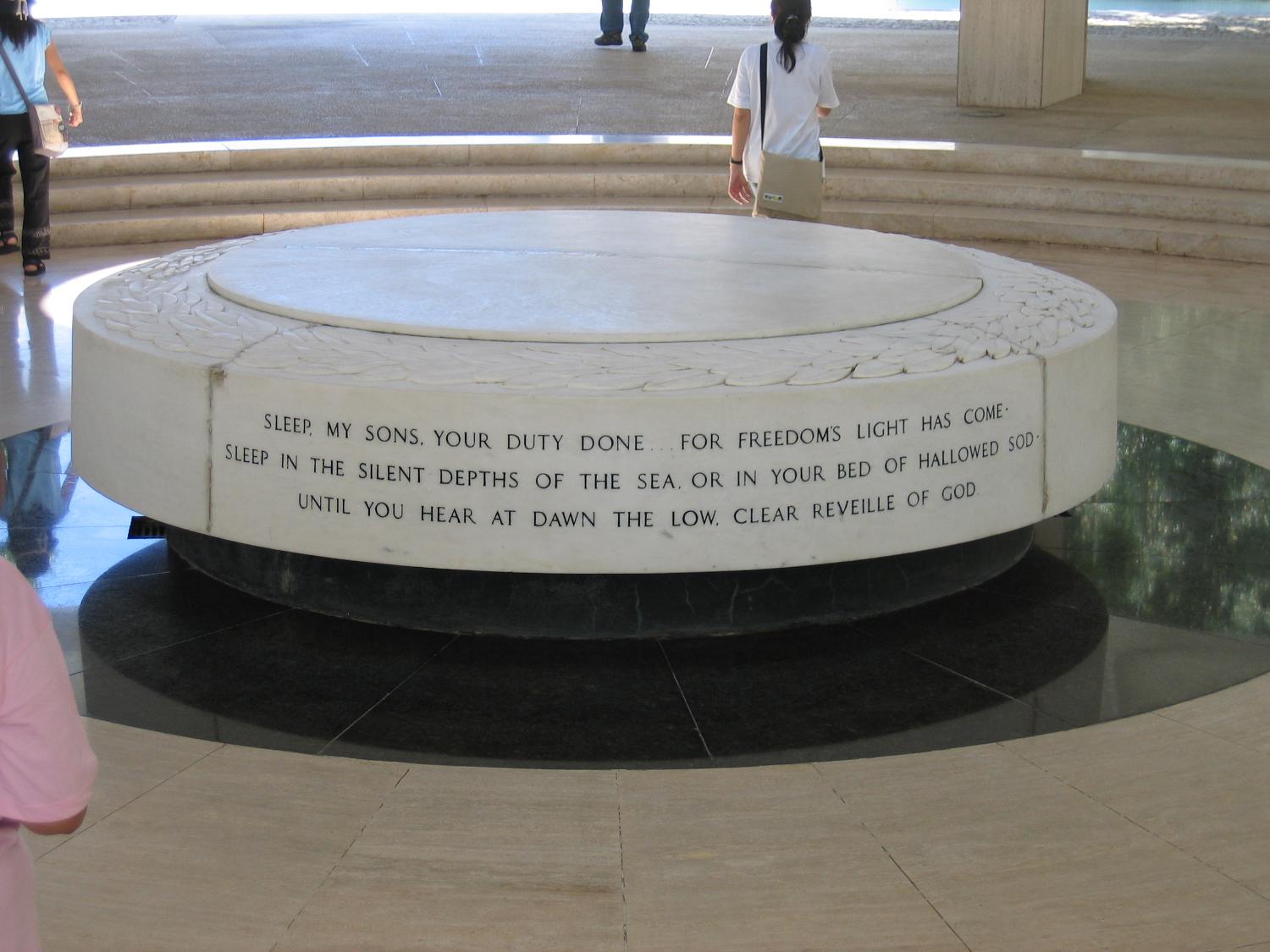

After two weeks of negotiating, sniping and fighting, Saudi Arabia secretly brought in French counter-terrorism commandos to aid in a final assault on the mosque. The hostage takers and the hostages had moved underground into tunnels and catacombs. Reportedly using chemicals, the combined Saudi and French force mounted a final assault. Some 250 people were killed and 600 were wounded, and the battle left at least 25 Saudi soldiers and more than 100 rebels dead. After it was all over, some 65 rebels were publicly beheaded.

During the siege, thousands of Saudi Shi’a living in the eastern provinces took to the streets, inspired by the Grand Mosque attack. Riots broke out and Aramco facilities were attacked. It took Saudi authorities until mid-January to subdue the uprising.

An interesting outcome of the assault on the Grand Mosque is that the Saudi monarchy adopted conservative Wahhabism as the official ideology of the state, essentially implementing many of the positions of the insurgents. Women are prohibited from driving or appearing on television, music is forbidden, all stores and malls are closed during the five daily prayers. A royal decree also says that there were to be “no limits … put on expenditures for the propagation of Islam.” Saudi Arabia becomes—and is—the problem and the birthplace of 9/11.