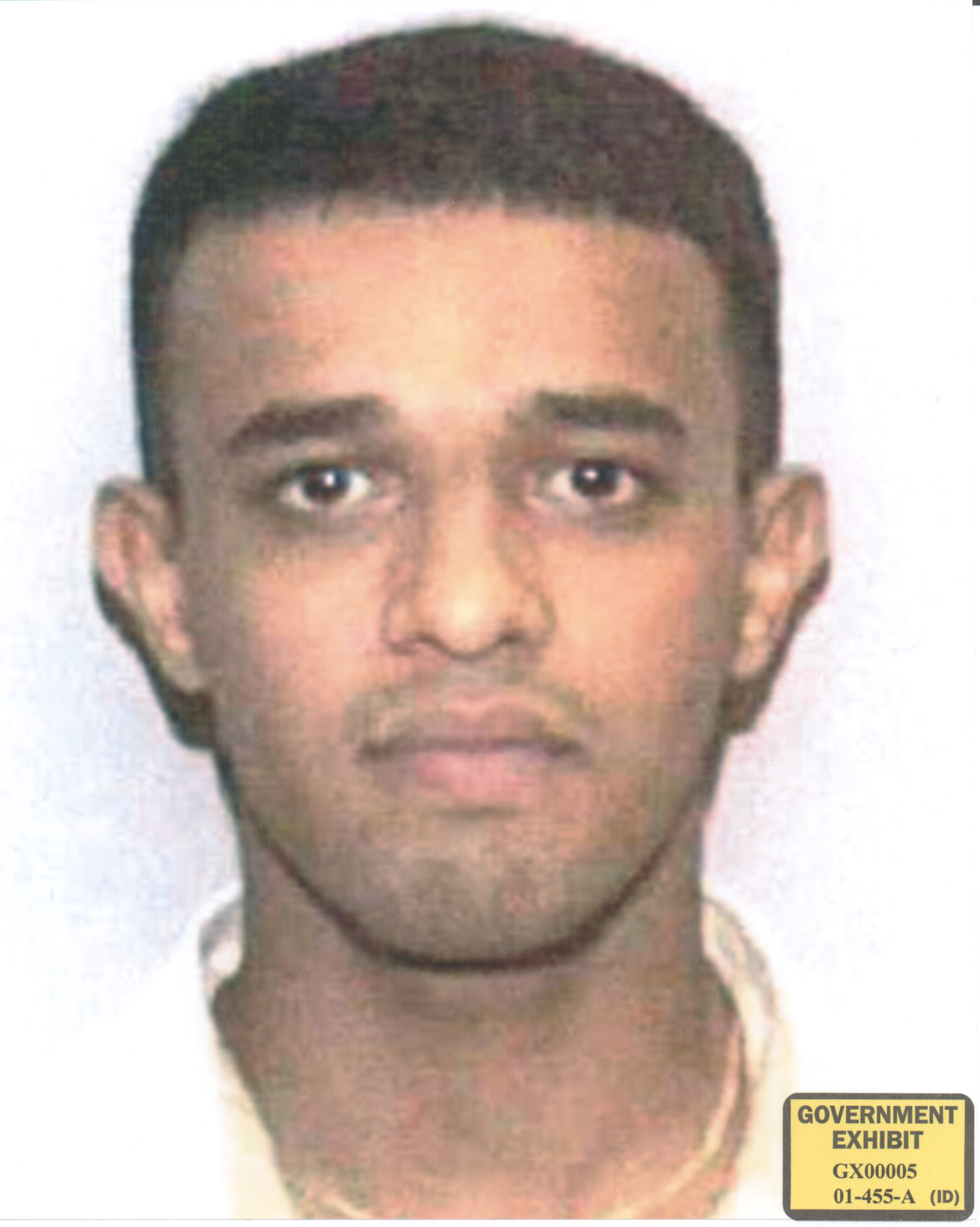

The so-called “Millennium Plot” is first detected, leading to the arrest of numerous plotters in Amman, Jordan. Jordanian intelligence uncovered the al Qaeda plot to attack the Radisson Hotel as well as other sites on the night of December 31/January 1, linking local extremists to Abu Zubaydah, an al Qaeda operative then-considered to be Osama bin Laden’s top terrorist planner.

When Zubaydah was apprehended in Pakistan in 2002 (and severely injured in a fire fight), he was characterized as “chief of operations” for al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden’s “number three” with the assumption that he was the main 9/11 planner. He wasn’t of course—that was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. But he would go on to be the first captive to be water boarded and tortured at CIA black sites.

As an interesting aside: after 9/11, many would report that Abu Zubaydah made a mistake and said in an intercepted telephone call that “the grooms are ready for the big wedding,” a tip-off which U.S. intelligence had already determined was a reference to an attack. (The Cell, p. 214) The 9/11 Commission reported, though, that Zubaydah actually said “the time for training is over.” (9/11 Commission, pp. 174–175).

Somehow then—and even now—terrorism experts think it is effective to stress that al Qaeda operatives make mistakes, or they don’t understand Islam, or were “failures”—such as that the Hamburg Three did poorly in pilot training—to delegitimize when none of those things seem to make a bit of difference in their ability and willingness to continue to attack. Nor do they dissuade others from joining their ranks.