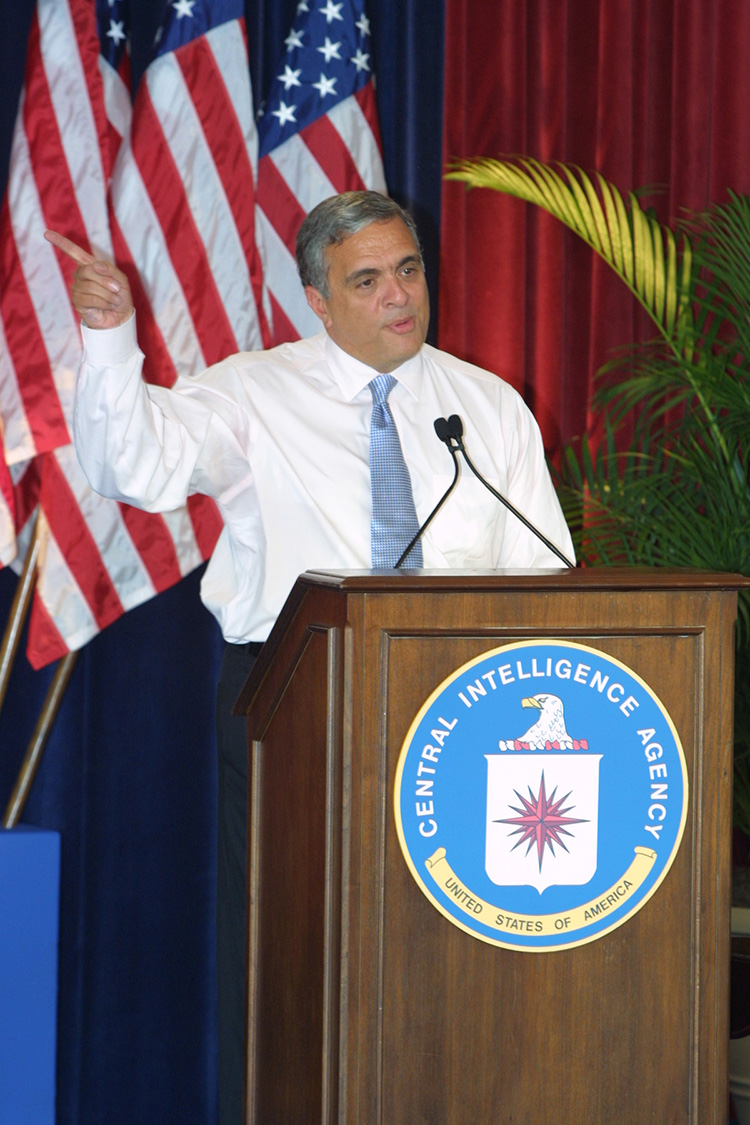

President Clinton signs additional covert action authorities for fighting al Qaeda, including expanding the number of individuals who were subject to capture operations. The formal presidential “findings,” a series of six Memorandum of Notifications, built upon previous (July 1999) covert action authorities already granted to the CIA.

Authority to undertake capture operations are specified by individuals and by country as to what assistance and circumstances the Agency can seek foreign government (and foreign organization) help. There are no “lethal” authorities per se, though obviously in 1998, cruise missile attacks against Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda sought to kill the leader.

CIA Director George Tenet is also instructed to develop additional capabilities beyond those already granted in 1999, such as strengthening relationships with the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance and Uzbek groups in Afghanistan. Another Memorandum calls for covert action to fight the expansion of al Qaeda into Lebanon.