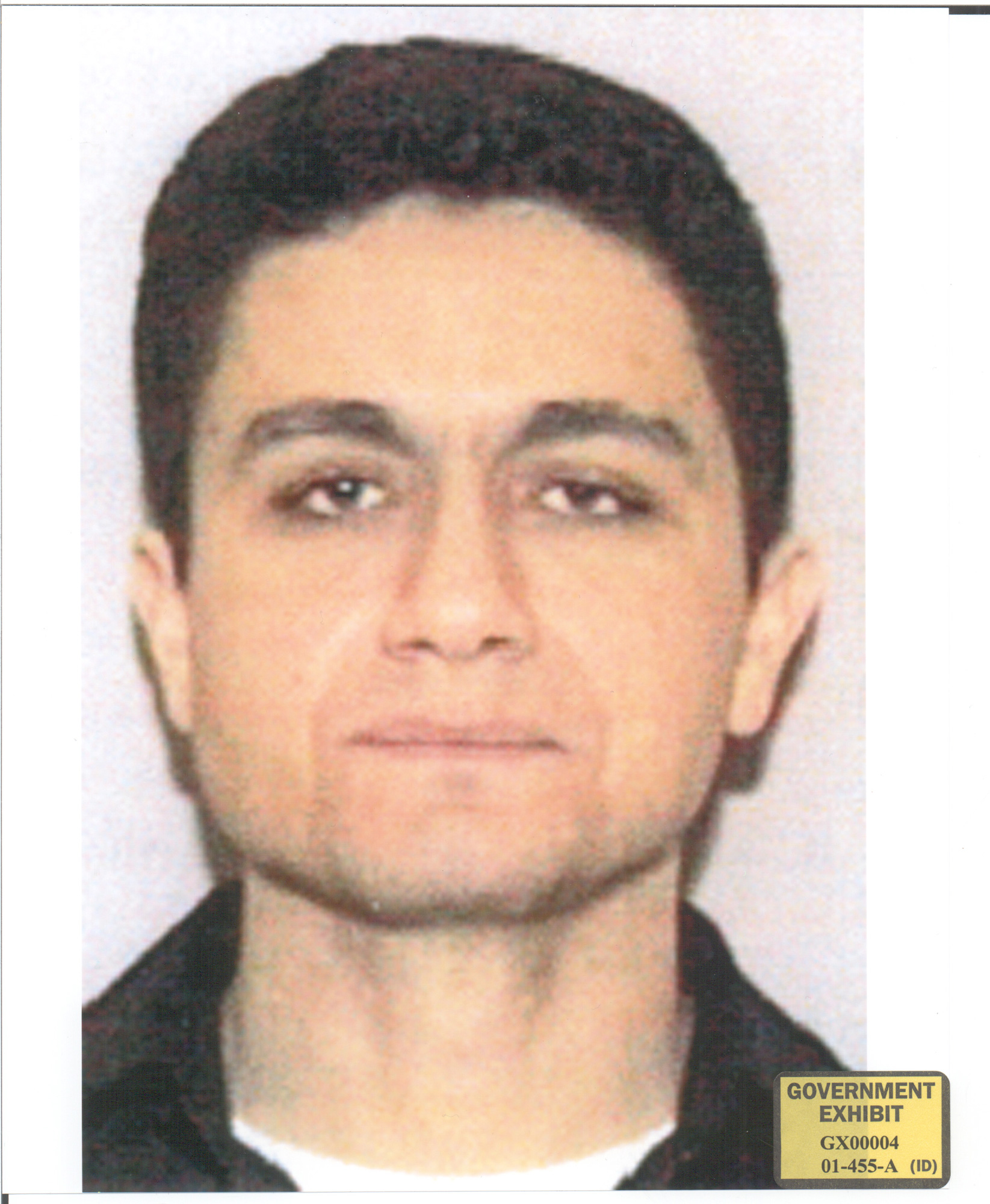

Mohammed Atta and Marwan al-Shehhi enroll in flight training at Jones Aviation in Sarasota, Florida. It is the second primary flight school, after Huffman Aviation, that they attend. They both fail their first tests and leave the school on October 6.

The 911 Commission will later comment—more than a dozen times—that throughout flight training the two struggled with poor English, failed their instrument rating tests, and scored badly in tests when they ultimately received their initial commercial pilot’s licenses in December 2000, as if any of that somehow made any difference. Perhaps such a record might have provoked school officials to question the Middle East men’s intentions, or even report to authorities, but as a matter of skill, evidently the two flew well enough to achieve their objectives.